2020-02-02, Le Matin Dimanche by Jean-Jacques Roth

«Mais Schubert, c’est un Everest! Celui que tous les chanteurs ont envie de gravir. On n’est pas sur la virtuosité, on est sur la couleur, l’articulation, le phrasé. C’est un répertoire qui requiert un contrôle absolu, mais en même temps il faut se libérer pour aller chercher l’émotion, le moment suspendu. C’est écrit par un ange…» […]

Source/Read original text: [x]

Translation to English

This is a fan translation; no infringement of copyright is intended. We believe it fulfills the criteria for “fair use,” discussion and study. Translation by *L

Philippe Jaroussky, Kamikaze Angel

The French countertenor, worshipped on the entire planet, abandons the Baroque heroes for a little while to venture in the footsteps of Schubert and his broken-hearted melodies. We met in Paris.

JEAN-JACQUES ROTH. PARIS

jean-jacques.roth@lematindimanche.ch

You will find few singers to be available for an interview within three hours of an important recital in front of ‘Tout-Paris’. You will find even fewer that combine such a friendly and open character with such sharp intelligence. That makes Philippe Jaroussky not only a rare specimen within his vocal register alone; he is also an exceptional man for his simplicity and genuineness, light years away from the vanity with which his triumphs could have inflated him.

He joined us in the bar of a hotel opposite the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, before the recital he was about to give there and which he will present soon at La Chaux-de-Fonds – a concert organized by the TPR in close collaboration with the Société de Musique – as well as at the Sommets musicaux de Gstaad. He will sing Schubert’s Lieder, which no countertenor has dared to tackle before him. He is nervous, all the same. “It may be the most difficult thing in my career.”

Viral video

Let’s go back to 2007. Jaroussky, not yet 30 years old, has just been crowned at the Victoires de la Musique and sings “Vedro con mio diletto” on live TV, a Vivaldi tune charged with amorous rapture. If a voice is to welcome us to paradise, we would like it to be this one: this celestial timbre, this fluidity of honey and this sensitive expressivity.

The video immediately goes viral. It has been viewed over 2 million times, a record for an opera tune. Immediately, the status of the singer changes. Jaroussky becomes the benchmark countertenor, a sort of male Cecilia Bartoli – they performed together and she made an appearance on his latest album, “Passion”.

Last fall, marking the twenty-year milestone of his career, Philippe Jaroussky entered the Musée Grévin and the Petit Larousse. He has read that tonight, to hear his performance, wealthy enthusiasts took the plane from Tokyo and Hawaii. Too many laurels, too many fans? “It may have scared me, but now I think of it as a chance. Twenty years that it lasts! I was talking about it with a colleague who has a career similar to mine: we were delighted to always have commitments, always an audience! “

He worked for it, of course, and like a madman, too – aided by his passion and by being a diligent student. Wherever he goes, Jaroussky can’t help it: he’s the darling. It started with the family, then at school. Since he sucked at sports, he developed tactical friendships with the dunces of the class. He also developed a skill for self-mockery which he calls his “engine of social integration”, which in turn facilitated his access to the eccentric roles of the Baroque.

Setbacks were part of the game as well. He starts to play the violin first, reaches a very good level but he reaches an obstacle. Excellence remains out of reach. The voice? But at first, it hardly impressed Nicole Fallien at the Conservatoire, who is still, twenty-two years later, his teacher. “It’s pretty … but it’s small!” she said when she received him in her class.

“I think there is a certain attraction, in our time which opens itself to non-binarity, for this voice between two sexes”

Philippe Jaroussky, countertenor

Small but very pretty anyway. From there, Philippe Jaroussky works to lengthen his breath, to enlarge his volume. He immerses himself in the manuscripts, learns all about baroque music. So when “Vivaldimania” arrives, this resurrection of the Venetian composer in the 2000s, it plucks him at the point of perfect maturity and offers him his “signature” roles.

With countertenors, however, it’s epidermal: either they fascinate or they cause rejection. Philippe Jaroussky is well aware of the divide caused by “the men who sing like women”, as he says himself. For the past twenty years, however, this high-pitched voice has fueled a hype. We ask him why: “There is this idea that people have of the castrati – which the motion picture ‘Farinelli’ has described well. This ambiguity is projected on us, while the vocal technique of the castrati was different due to their mutilation. They had a very developed thorax and smaller vocal cords, which gave them an exceptional breath length. That said, I think there is a certain attraction, in our time which opens itself to non-binarity, for this voice between two sexes – for the ambiguity of a sexual personality with a prepubescent voice.”

But how does this voice, which seems so delicate, age? “We don’t know: the countertenor voice is quite young, we lack perspective. The golden age is between 25 and 45. However, despite my “babyface”, I will be 42 years old soon. I have to work even more to stay at the best level and keep my flexibility. For the rest, we will see. But I don’t see myself in baroque roles after 60! ”

They are, however, the ones his audience demands. The flamboyant heroes, in victory and misery, with their virtuoso vocalizations and their heartbreaking complaints … “I still have many projects in this field. But I also want to take people to other musical and metaphysical spaces. I was a musician before I was a singer. Singing is a passage in my life. I founded an ensemble that I conduct, the Ensemble Artaserse, as well as an academy to democratize classical music by welcoming young people who would not have any access to it. And in the end, there might be a discrepancy between what I tell you today and what I end up doing. We all know it’s hard to quit …”

Discomfort zone

And then there are the side steps. A few years ago, Philippe Jaroussky first left his comfort zone to sing French melodies from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. composed on poetry by Verlaine. He has also participated in the creation of projects, including the opera “Only the Sound Remains” by Kaija Saariaho, composed specially for him.

This time, he set sail to yet another musical continent: Schubert’s Lieder. These short melodies accompanied by the piano, where the composer concentrated the most intimate of himself, the pain of a wounded heart as well as the evocation of happy memories.

No countertenor, however, has ever docked on these shores which are reserved for low masculine voices, basses or baritones, even if tenors and a few women have also sung them. “This is my kamikaze side! I have this reputation of an ideal, slightly stuffy son-in-law, but in music, I have often taken risks.

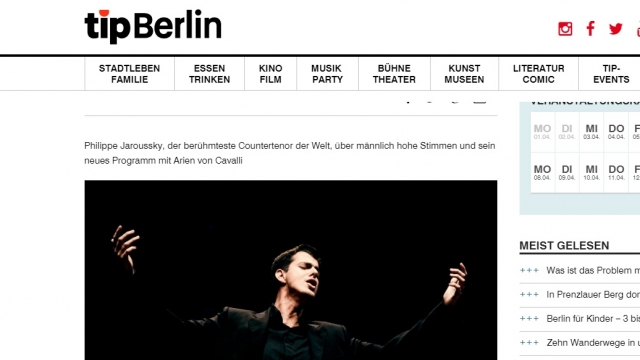

Philippe Jaroussky: “I am wary of the modesty of those who have succeeded, including mine.”

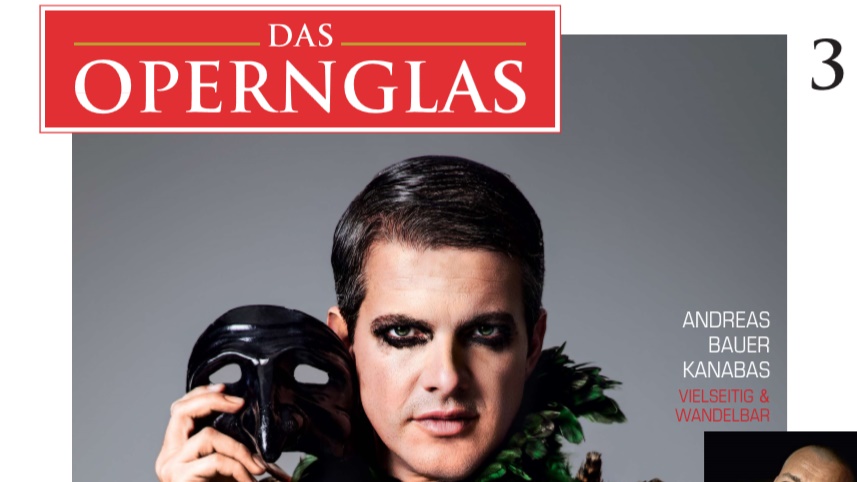

Image credit: Léa Crespi / Pasco

I have always considered myself a musician rather than a singer. And since I’m no more stupid than anyone else, why can’t I express poetry set to music? ”

Hearing Jaroussky in Schubert is a shock and he knows it. It takes time to adapt to taste these Lieder perched so high, set in seraphic light where feelings at first struggle to be embodied. But soon the magic happens, Jaroussky relaxes, his pianist Jérôme Ducros works wonders: the emotion flows freely, the room melts and calls for endless bis.

He opened this recital in Berlin. “When I stepped onto the stage of the Staatsoper, I was dizzy. How dare I speak German in front of an audience who knows it by heart? But it’s still my kamikaze side. I go out of my comfort zone and part of my audience does as well; I’m taking a risk vis-à-vis one who is waiting for me in Handel or Vivaldi, but also vis-à-vis the audience that knows these Lieder very well and that I might disappoint. “

He worked two months non-stop on Schubert. “In general, for baroque operas, I have a fairly complete vision of what I want and I don’t listen too much to what others have done with it. For Schubert, I listened to everything. Hotter, Wunderlich, Fischer-Dieskau, Goerne or the one I prefer, Christian Gerhaher … “

We are astonished all the same that these melodies seem more arduous to him than the baroque vocalizations which he dominates with such dazzling virtuosity – as a student, his nickname was “the machine gun”. “But Schubert, it’s an Everest!” The one that all singers want to climb. It’s not about virtuosity; it’s about colour, articulation, phrasing. It’s a repertoire that requires absolute control, but at the same time, you have to free yourself to go and find the emotion, the suspended moment. It’s written by an angel … “

Therefore, since two months ago, Philippe Jaroussky has been in deep immersion. “I worked a lot, I asked myself a lot of questions, I drew on resources that I did not know, I went through moments of discouragement and doubt. But I don’t regret having done it. It takes me to discipline my life even worse than usual. I eat, I sleep, I revise my texts, I speak as little as possible and I warm up shortly before the concert to stay at the peak. But singing this music makes me feel good. ”

“Schubert asks me for an even worse discipline than usual. I eat, I sleep, I speak little, I revise my texts”

He also says he would like people to “come out with a slightly changed outlook on life” from such a recital. “We run everywhere, so landing two hours to perceive time in another way – that matters, doesn’t it? I find it a shame that a large part of people does not have access to this. The more time passes, the more I find it a privilege to be able to be touched by music.”

Always modest, he also says that he “does not yet completely dominate” his subject, that he still has to work. Every recital – he will have given 14 by the end of his tour – he is making headway, after which he will record an album. Is he again in the skin of the cherub who does everything right? “I am wary of the modesty of those who have succeeded, including mine,” he said in the interview book he just published (“Seule compte la musique”, Éd. Papiers Musique). The ultimate elegance of a musician who knows everything about his weaknesses, as well as his resources: Jaroussky’s greatest talent may be that of being himself.

LISTENING

At La Chaux-de-Fonds (NE), music room, February 5. At the Sommets musicaux de Gstaad (BE), Rougemont church, February 3.

Source/Read more: [x]