2016-08-29, Place d’Opera, original by Martin Toet

Source/Read original: [x]

* This is a fan translation; no infringement of copyright is intended, no profit is being made. Translation by RvO*

Jaroussky’s return to Utrecht is a big party

(Jaroussky’s retour in Utrecht is groot feest)

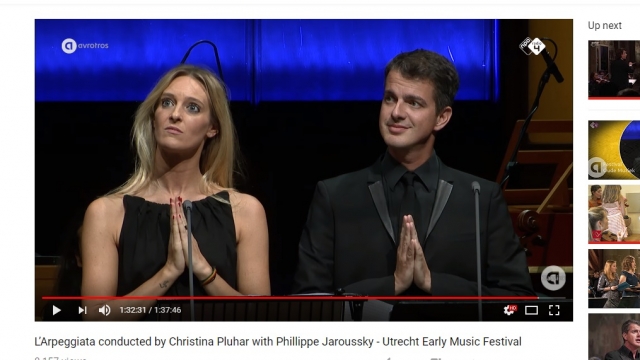

In seventeenth-century Italy, the roles of performer and composer were often united in one person. With unprecedented joyful and outside-the-box [the dutch as well as the German word “vogelvrij”/”vogelfrei” means “outlawed” as well as literally “free as a bird”] musicianship, Philippe Jaroussky and his ensemble Artaserse somewhat made these times come to life on Saturday at the Festival TivoliVredenburg. A memorable concert of a vocal superstar.

“Che città!” What a city! This Saturday, countertenor Philippe Jaroussky sang this almost as surprised as the errant page wandering through Fez in Cavalli’s L’Ormindo. The exasperated sigh could also hint at Venice, the theme of the Festival Old Music in Utrecht. Or at the Cathedral City itself… The overwhelming offer in numerous locations is hard to overlook, even for the true enthusiast. The bulky program book and the numerous helpful staff at the cozy Festival Center provide some help.

Ten years ago, Jaroussky surprised at the Utrecht festival with jazzy interpretations of Claudio Monteverdi’s madrigals. This time, with his own ensemble Artaserse, he performed music from the Italian “Seicento,” music from the seventeenth century at the TivoliVredenburg, [a program] centered around the lively opera scene in Venice.

With the opening of the first commercial theatre in Venice in 1637, the young art form became full-fledged, shedding its ideological feathers. They were done with the sublime, Arcadian themes served for the nobles and humanists in Florence or Mantua. In Venice with its lagoons and islands, everything centered on the the mortal man, with all his passions and weaknesses, nowhere embodied better than in L’incoronazione di Poppea by Monteverdi. His pupil Francesco Cavalli continued the dramatic thread with a long series of successes.

From Poppea, Jaroussky sang “Oblivion soave,” a lullaby sung by the old nurse Arnalta – not in a light and comedic way, as it presumably was rendered in 1642, but with ear-caressing tenderness and unending sustained notes, dissolving in dying string sounds.

The theme of sleep dominated most slow numbers, such as Endimione’s night prayer to Diana in La Calisto, and – awakening from Amor’s grip – the one of the hero in Giasone. These two works by cavalli were right up Jaroussky’s street, but not because of his soporific singing! On the contrary, it is hypnotic how, seemingly effortless, his smooth golden sound ascends to heights that leave other countertenors gasping for breath. In every detail, Jaroussky showed his masterful interpretation of the text. With one word alone, “Fermate,” he aptly expressed Giasone’s overtired passion.

Exemplary phrasing and articulation also graced the big slumber scene from Giustino Legrenzi’s Giustino, a once wildly popular opera of the same name. Jaroussky went into the recitative with a fascinating dialogue with the viola da gamba of Christine Plubeau, a colleague of the first hour at [the ensemble] Artaserse. With twelve persons, the instrumental structure differed probably not so much from the “orchestra pit” in the Venetian theatres (the singers, at the time, used up most financial resources). But what richness of colours rose from this group of strings and the pluckers of harp, theorbo and guitar! Yoko Nakamura laid out a modest basis on the harpsichord and the organ, while two woodwinds with their (un)curved cornetti ensured color. Literally at the centre stood the playful percussionist Michèle Claude. Musical leader Jaroussky, during the instrumental intermezzi from, among others, Marco Uccellini, could watch the joy of playing with confidence.

Violinist Raul Orellana deserves a special mention for his rendition of the Sonata La cesta, by Pandolfi Mealli, composed in the “stylus phantasticus.” Fantastic indeed, these virtuosic but delicate antics, gradually supplemented by Plubeau in a typical Baroque lamento style on the gamba. The Sonata is a musical portrait of the composer Antonio Cesti, of whom Jaroussky performed a yearning plaint of love.

A diverse program indeed, but deliberately constructed with such a tight fit that applause had almost no chance. Of course, in between all the lamentations, there was also space for energetic fast paced numbers. After the break, Jaroussky’s coloraturas were even smoother than before. Long live the surtitles, so that in Cavalli’s warlike “All’armi mio core,” it became clear how the strings and horns respectively symbolize whistling arrows and clattering weapons.

A pity that the translation was missing for the so expressively interpreted recitative of “Dal mio petto” from Agostino Steffani’s Niobe. Together with the intense lament from Luigi Rossi’s L’Orfeo, written shortly after the death of Rossi’s wife, this belonged to my personal highlights. Above all, that beautiful bridge passage to the da capo! In a powerful show of musicality, Jaroussky filled the relatively simple melodic lines with bold ornaments. Here blurred the border between composer and performer; each repeated phrase sounded like new and seemed to be improvised on the spot.

The enthusiasm of the audience knew no bounds, and was rewarded with three encores. Monteverdi’s immortal “Si dolce è’l tormento” I rarely ever heard worked out so subtly, in flawless interaction of singer, cornet player and violinist. As an official finale, Steffani’s ‘ Gelosia, lasciami in pace ‘ was already a swinging jam session, but in the reprise it was all brakes-off. Percussionist Claude stole the show and the exchange between her and a quasi-offended Jaroussky let everyone return home with a broad smile.