2015-02-20, Concerti, concerti.de

Generationen ehemaliger Schüler denken mit Schrecken an die Zeit, als sie vor versammelter Klasse auswendig ein Gedicht vortragen mussten. Für Countertenor Philippe Jaroussky indes wurde diese pädagogische Maßnahme dereinst zum Schlüsselerlebnis: Ein Poem Paul Verlaines schlug den damals zehnjährigen Schüler regelrecht in seinen Bann. Ein Vierteljahrhundert danach hat der Sänger nun ein Doppel-Album mit Liedern nach Gedichten des französischen Lyrikers veröffentlicht.

Source/Read more: concerti.de

digital edition edition here

The following is not a professional translation; no profit is being made, no infringement of copyright is intended.

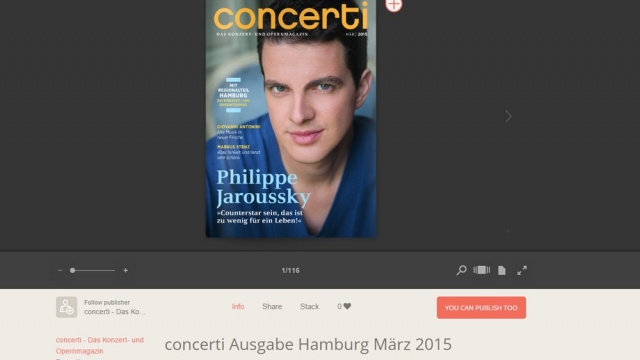

“Being a star countertenor is not enough for one lifetime!”

He is the most popular of his kind: Philippe Jaroussky about star cult, sabbaticals, and the difference between great voices and great artists

by Teresa Pieschacón Raphael

(caption 1) From violin to singing: Jaroussky first learned to play the violin before he started singing

(caption 2) Even as a child, at home, he preferred to sing the high notes

With horror, generations of former students recall the time they had to recite a poem by heart in front of their classmates. However, for countertenor Philippe Jaroussky, this educational measure proved to be a formative experience: A poem by Paul Verlaine veritably put the then 10 year old student under a spell. A quarter of a century later, the singer released a double-album with songs based on the French lyricist’s poems.

Mr. Jaroussky, unlike pictured on the cover of your new CD, we are not at Verlaine’s favorite café, but at a banal one at an airport. But where is your glass of absinthe?

Oh, perhaps I’m too well-behaved and disciplined for that; I don’t need this kind of “inspiration” – maybe unlike Paul Verlaine. When I’m not on stage, I lead a pretty normal life… Recently, a photographer even told me I seemed too “nice and gentle,” and suggested I should pose as the “bad boy” for a change.

A “bad boy” – this term surely applies to Paul Verlaine, a drinker who squandered his parents’ property, and who, intoxicated by drugs and alcohol, attempted to kill his mother…

… and who yet, at the same time, was a genius!Genius and madness, this is an ancient an ancient romantic topos; do you believe in it?

I would compare Verlaine to the painter Caravaggio…… Whom you represented in 2012, in an opera composed for you by Suzanne Giraud…

… in his life, there also was this mixture of light and shadow – and Caravaggio brought it to the canvas. Perhaps Verlaine’s incredible talent had to be compensated by the shadows in his life. It is this paradox, that talent and beauty, in some personalities, carry the seed of self-destruction. Maybe the two go together in some way in such a highly sensitive personality – which does not necessarily mean that the reverse is true, that if you drink a lot and take drugs, you will inevitably be creative. That is to say, I am firmly of the opinion that this is not the case.How should we imagine the artists of the 19th century Parisian Bohème around Paul Verlaine?

Why is this world so fascinating for us? We believe that people had greater freedom – and yes, I do believe that they had. At least, they took it for themselves, were less compromising. But life has changed; we had World War I and II which brought about a change of social structures, but equally, the attitude has changed. Today, it is important what you own: the new car, the new iPhone. We all want to own – which has me wondering why so many people buy tickets for my concerts, even if they can own neither me nor the music.Each and every composer of the Belle Epoque was inspired by Verlaine. It is said that his poems have been set to music over 1,500 times.

He was kind of the Metastasio of his time. [Translator’s note: Metastasio was an immensely productive librettist in Baroque times, famous for his “Artaserse,” “La Clemenza di Tito” and others. His poetry has been set to music even by Schubert, (“Pensa, che questo istante.”)] Everyone wanted to set one of his poems to music. He was like an authority, like a classic. Everyone wanted to penetrate Verlaine’s personality, and only succeeded in revealing their own – because, surprisingly, the mood that different composers perceived in one and the same poem, often varied wildly. Take Verlaine’s D’une Prison (“In Prison”)…… the same poem that you had to learn by heart in school, when you wear ten years old, a pupil in the Paris suburb of Maisons-Laffitte…

… yes, that was my first contact with Verlaine. I remember that I liked it very much, that it was beautiful. These lines! The sky is blue, it is quiet, the prisoner looks out of the window and hears the church bells. Especially the last line of the poem burnt itself into my mind: “What have you done… with your youth? [Translator’s note: “Dis, qu’as-tu fait, toi que voilà, / De ta jeunesse?”] While you can literally hear the church bells ringing in Fauré’s setting – he imitates them in the music – the music of Reynaldo Hahn manages to sketch the whole atmosphere with a few notes, culminating especially in this last line, this existential moment: What have I done with my life? Did I waste it, maybe? It’s very dark. The sentence continues to haunt me to the present day.Yet the critics like to call you the “radiant god among countertenors.” [Translator’s note: “Strahlengott” was a word first used for Jaroussky by the German magazine “The Spiegel” I believe. It doesn’t really exist apart from him; it is his own title. There is one German poem where the word appears; I put it at the end of my translation.] So what? That’s not coquetry, but the essence of life doesn’t consist of being famous! That isn’t a normal life, on stage, where 2000 people are looking at me, or is it? I am taken everywhere and I am fetched again, I am cared for as if I was a baby, from my home to the car, from the car to the airport, fromthe airport to the rehearsal room, from the rehearsal room to the stage, from the stage to the hotel… There is no way you can stay normal under these circumstances! It is an alluring lifestyle, but when you start to believe that this was real life, you’re in danger.

Was this one of the reasons why you took a sabbatical two years ago?

I didn’t want to end up turning 60, and just then realize that I have been the star countertenor Philippe Jaroussky all my life. That is not enough for a lifetime! And I wanted to be anonymous, travel to places where no one recognizes me. That has been healthy. I needed some time out to relax; I needed to become human again. I was away for eight months, and I hardly ever sang. I have been to south America and New Zealand. Before, I talked about it a lot in the media, because, of course, I didn’t want any rumours to start spreading.Back to Verlaine. You refer to the selection of songs, from Saint-Saëns up to chansonniers like Ferré, as a “secret garden.” A different repertoire than one would expect from a countertenor.

Oh yes, and I am curious about the reception. Already when I recorded “Opium,” where I first sang songs based on poems by Verlaine, I surprised a few people who rather expected me to sing some virtuosic Baroque arias, especially in France. I love surprises, but that isn’t the reason why I made this double-album: All these years, I almost exclusively sang Italian – there is no repertoire in French Baroque for me. Just because I am a French singer though, I always had a great desire to sing in my own language.And yet your name sounds rather Russian. Do you have Russian ancestry?

Yes I have! My surname Jaroussky really means: I am a Russian.And are you really?

My grandfather, who was Russian, left the country before the revolution in 1917. I myself don’t speak a word of Russian, unfortunately, it is so far away. Sometimes I feel a little bit Russian, and when I was in Moscow and St. Petersburg, I had the impression that there was something that really touched me. In addition, the music is is very dear to me, Shostakovich, the choirs …… the famous Russian basses…

… yes, as well, even if I am singing in a different vocal range.You are a countertenor. Now, the “law of nature” demands that women sing high and men sing low – how did your father like your voice?

My mother instantly loved my countertenor voice – my father was rather surprised, but he didn’t react negatively at all. He rather was concerned if I could handle this life as an artist. Both accepted it when I gave up my violin studies and devoted myself entirely to my singing career. It wasn’t easy because I started very late. But I was lucky; I instantly got some jobs, and they saw that I could prevail.Is it right to conclude that a voice that is big in volume maybe is really not so terribly important after all regarding the success of a singer?

Many people claim that there weren’t any great voices any more today. How I hate this sentence! We don’t need great voices; we need great artists – which isn’t the same thing! You can have a great voice, and still be a lousy artist.***

*) [Translator’s note: “Strahlengott”]Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, from “Letzte Gaben”. Nachgelassene Blätter. Hrsg. v. Levin Schücking. Hannover, 1860.

http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/letzte-gaben-2842/12

http://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/book/view/droste_letzte_1860?p=46The poem this is from is sometimes titled “Stille Größe” (Quiet Grandeur), sometimes “Einer wie Viele und Viele wie Einer” (One like many and many like one), but I believe none of these titles is by Droste-Hülsoff herself.

Last verse:

Behütet euren stillen Schatz

Laßt uns das sönnenöde Land!

Laßt uns den freien Bühnenplatz

Und sterbt im Winkel unbekannt;

Einst wißt ihr, was in Euch gelebt,

Und was in dem, der Euch gehöhnt;

Einst, wenn der Strahlengott sich hebt

Und wenn die Memnonsäule tönt.Translation (just mine:)

Annette von Droste-Hülsoff, from “Last Offerings,” literary remains, Editor v. Levin Schücking. Hannover, 1860Guard your secret treasure

Leave us the sun-barren land!

Leave us the empty space for a stage

And die in a corner, unbeknown;

One day you will know what has lived in you,

And what in the one who derided you;

That day when the god in shining rays arises

And the Colossi of Memnon will sound.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colossi_of_Memnon