2019-03, Concerti, by Christoph Schmidt

“Yet another life goal of mine for many years has been to become a conductor. In three or four years, I am going to conduct my very first Baroque opera – something I am really happy about. That means, I am going to be a singer and a conductor at the same time. At first, both activities will mix, and by and by, I want to sing less and less in favor of expanding my time at the baton. I want to take more responsibility for my musical message.”

Translation to English

This is a fan translation; no infringement of copyright is intended. We believe it fulfills the criteria for “fair use,” discussion and study. Translation by *L

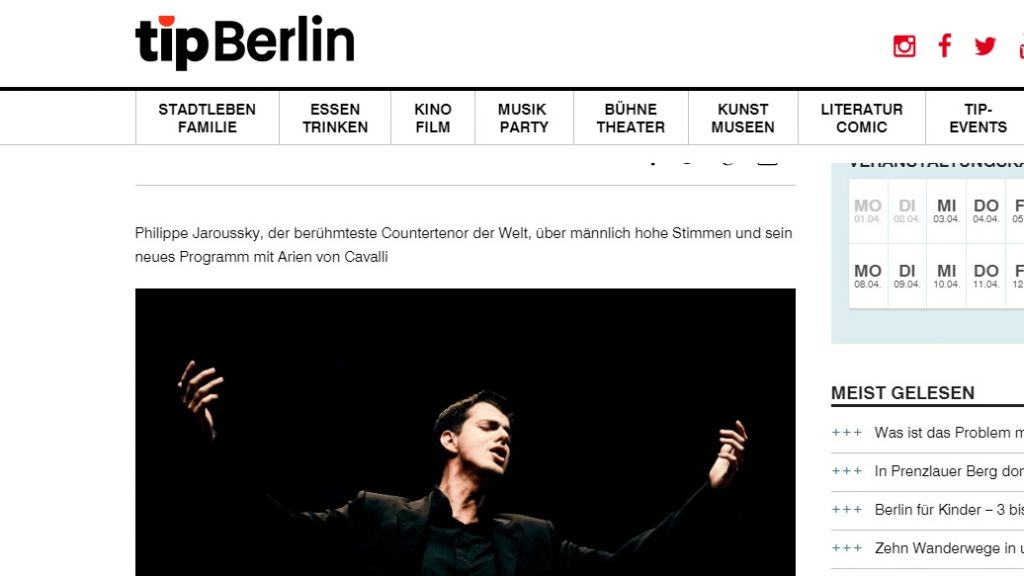

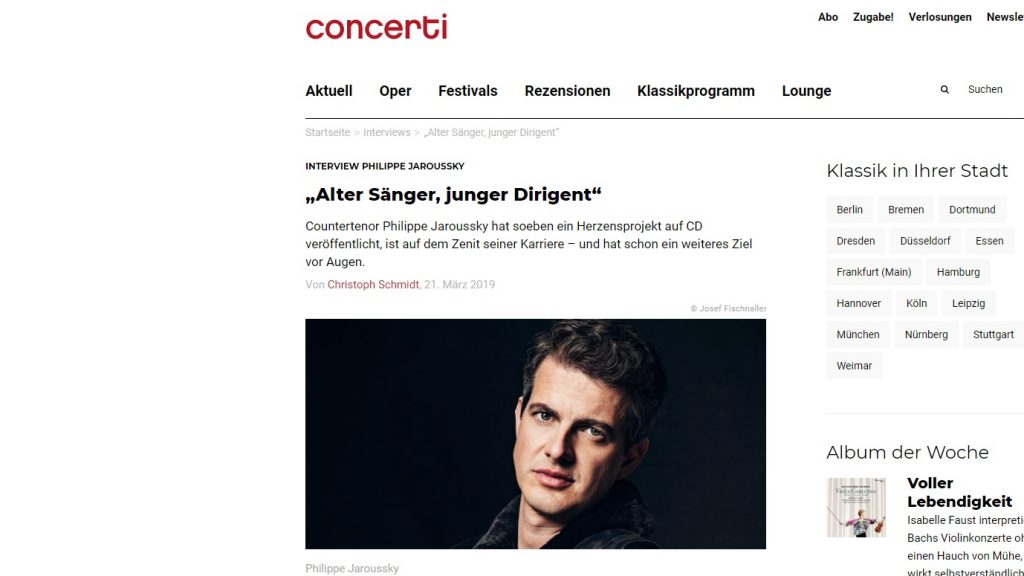

Interview Philippe Jaroussky

“Old singer, young conductor”

Countertenor Philippe Jaroussky has just released a project very close to his heart, is at the zenith of his career – and already has the next goal in mind.

By Christoph Schmidt, March 21, 2019

It doesn’t occur very often, that an asteroid is named after an opera singer. After numerous international awards, Frenchman Philippe Jaroussky also accomplished this one.

At the height of his career, the 41-year-old is also thinking about radically changing his musical career. All while the 41-year-old, on the peak of his career, is thinking about radically changing the course of his career.

At the beginning of the new year, you wanted to take a sabbatical. What do you do, if you do not sing?

Philippe Jaroussky: I stopped singing just before Christmas, with my next concerts being in March. However, I still had plenty to do and prepare: I needed to think about future projects and make decisions; I had to look after my academy, and last but not least, I had to put some thought into the upcoming programs in the near future. It’s nice to do these things in such a relaxed way because it allows you to focus. While on tour, I don’t find any peace for that kind of thing. Sometimes it’s just good not to sing, even though that’s my passion, because a break allows you to take a look at yourself from the outside and imagine what it would be like not to sing.

How often do you take such a break?

Jaroussky: It’s only my second time. It helps me to relax the voice and refresh the technique. Afterwards, I enjoy making music again all the more and, hopefully, I can pass on this joy even better to the audience. As soon as I start practising again during my morning shower, I realize: I’m ready to start again!

Do you also practice your baritone or exclusively the head voice?

Jaroussky: When I started, my singing teacher trained both registers because the baritone is closer to my speaking voice. It can be very useful to understand the mechanisms of the voice in this natural range in order to apply what you discovered to the countertenor voice. Since I’m not a tenor, the lower range of the countertenor voice are not exactly my specialty; it’s something I am working on continuously. Because on stage, for an opera, you also need the chest voice – and there, you only have one shot at an aria. When you’re recording a CD, it’s altogether different, and I end up doing nothing but singing for seven or eight hours a day; in a sense, it’s an entirely different job.

Almost every year, you release a new album. However, the death of the medium of the Studio CD has been foretold. How do you manage to help keeping it alive?

Jaroussky: My record label and I sometimes say we really should slow down. My last solo album was released in November 2017; in between, I have also been present on other recording. Fortunately, there is still a multitude of projects. Needless to say, as a singer, you want to record the most in the phase of your life when you feel in top shape. After all, I don’t know how long I am still able to record CDs.

Your new album, “Ombra mai fu,” quotes an aria from Francesco Cavalli’s opera Xerxes, which became famous by Handel. Who do you think is the better composer?

Jaroussky: Of course Handel’s “Serse” is the best version. Also, for the majority of audiences, Monteverdi is certainly more famous than Cavalli is. However, I chose the title to provoke a little – because, after all, the first version of this aria is the one by Cavalli! That makes you curious. It’s interesting that, for example, the first violins are not playing colla parte with the soloist, but higher. That’s ingenious and has its own charm.

Which other qualities do you perceive in Cavalli?

Jaroussky: I discovered him right at the beginning of my career, when I was in my early twenties. Even then, I was beguiled by the charm of this music; he has a distinctive personal style. It’s no wonder that currently, almost all of his operas are being performed. On the CD, I wanted to create a digest of the best arias and duets from all his operas, also to show the variety of his composing – from lamenti to extremely comical scenes. Even during his lifetime, his music was very popular. It is much simpler than Händel’s, and more fragile. Cavalli was writing very fast, and sometimes, he only notated the voice, and the bass line. Who, when, with whom, and with which instruments is actually playing together often remains for the musician to decide. Solely the instrumentation turns it into kind of a new creation. When it comes to Händel, most is fixed. That’s why I love early Baroque music so much – because it educates you in imagining the right sound, and prompts you to interpret the libretto.

You are considered a specialist in the field of Early Music. Are you also interested in contemporary repertoire?

Jaroussky: Of course; I have often had the opportunity to sing new pieces, because the countertenor has actually evolved into a modern voice type once more. My next CD project is going to include contemporary music, only with piano accompaniment, but it’s too early to talk about it.

You are now 41, have won numerous classical prizes and are performing all over the world. What ambitions, goals and challenges could someone like you still have?

Jaroussky: When you’re young, you have a lot of dreams. At the time, I never dared to hope I would sing at La Scala one day. You’re right; I’ve achieved much more than I thought. But more important is that you can choose what and with whom you sing. The audience is very grateful, and I would like to experience these moments more intensely, just because I do not know how much longer I can enjoy them.

Sounds a little hedonistic.

Jaroussky: That may be true, but if you want to sing, actually enjoying it is paramount. Yet another life goal of mine for many years has been to become a conductor. In three or four years, I am going to conduct my very first Baroque opera – something I am really happy about. That means, I am going to be a singer and a conductor at the same time. At first, both activities will mix, and by and by, I want to sing less and less in favor of expanding my time at the baton. I want to take more responsibility for my musical message.

Does that also give rise to your motivation for your music academy that you founded for children and young adults?

Jaroussky: I come from a family that was completely unmusical. My teachers told my parents to make music – so I started the violin. That changed my life. Twenty years later, I now have the chance to influence the lives of other children, positively, if I can. I was often asked if I thought that more should be done for musical education. I always agreed, but never actually did anything towards that ideal. I try to make up for this lack now at least with fifty students per year. And they don’t have to pay a cent for it.

Is that your kind of work-life balance?

Philippe Jaroussky: You can learn something from this for yourself! When you teach, you are forced to organize your thoughts, to express opinions, to sing something to the students. Some impulses also come from the pupils and students themselves. This shapes and enriches their own music-making immensely. And last but not least, it is a tremendous pleasure to be a teacher!

See Philippe Jaroussky’s “Ombra mai fu” from his eponymous album:

Album Tip

Ombra mai fu – Arien von Cavalli

Philippe Jaroussky (Countertenor), Emoke Barath (Sopran), Marie-Nicole Lemieux (Alt), Ensemble Artaserse

Erato

Source/Read more: [x]