2015-02-18, Brigitte

Obwohl er Sopran singt, sagt Countertenor Philippe Jaroussky entschieden: ‘Ich singe nicht wie eine Frau. Ich singe mit meiner männlichen Empfindsamkeit.’ Die wachsende Popularität von Sängern mit hohen Stimmlagen erklärt der 37-jährige Franzose in der neuen Ausgabe des Magazins BRIGITTE (Ausgabe 5/15, ab heute im Handel) damit, dass es eine neuen Begriff von Männlichkeit gebe. “Noch vor wenigen Generationen sollten Männer tapfer sein, nicht weinen, ihre Gefühle nicht ausdrücken. Doch jetzt haben wir starke Frauen und sensible Männer’.

Source/Read more: Brigitte

The following is not a professional translation; no profit is being made, no infringement of copyright is intended.

Peter Pan Is a Soprano

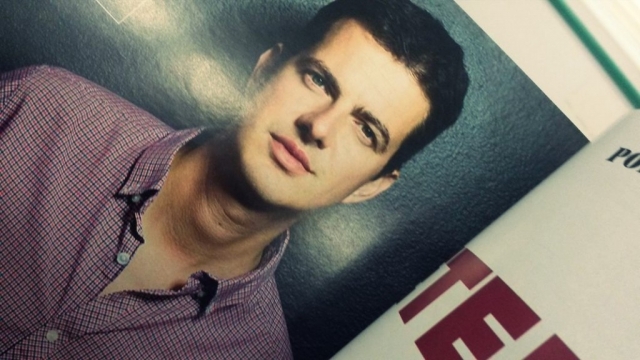

According to his fans, listening to him is like a drug. Philippe Jaroussky is a countertenor. His voice neither sounds male nor female, but always effortless and like deep feelings. A meeting with one of the biggest stars of Classical music.

Meike Schnitzler

First of all, Philippe Jaroussky says “sorry”. Sorry that on the table, there is a large pot of tea, next to it a selection of cold remedy and throat lozenges.The last thing that Jaroussky wants to come across as is a hysterical opera diva who is busy pampering and nursing her precious soprano voice every second of the day. Soprano? Yes, the 37-year old Frenchman sings in the highest vocal range. Something that, right on the spot, one wouldn’t believe, because his speaking voice is a light baritone, a little raspy, because of the cold.

The day before, he had a concert in Hamburg; tomorrow it’s Berlin. Not a good time for a sore throat. “Classical singers have to fill an entire hall without the aid of a microphone,” says Jaroussky. “Luckily, I don’t have a cough. Then it would be over with my kind of voice.” His sort of voice – this is a no-frills vocal organ, able to spiral higher and higher like a bird, then stooping, its purity burning itself into the listener’s hearts. A voice that sounds neither male nor female, for which some fans will travel around the globe not to miss any of Jaroussky’s concerts. Even the night before, among the audience who rewarded his Vivaldi arias with standing ovations and enthusiastic trampling, the singer recognized some of his greatest female admirers.

“For some of these people, the two hours of a concert are almost more important than they are for me. Some tell me that they need to hear me every day. That it was like a drug. That does sound strange, non?” the singer says, with a glance of genuine surprise. He concedes that the phenomenon was common in the world of Pop music. He could be glad – a Justin Bieber would have more problems in life by far. In the Classical world, however, Jaroussky is very close to the status of a Justin Bieber, although his fans tend not to be teenagers. “Most of them are women,” he says. “They give me chocolate or scarves for my throat.”

It is doubtful, however, whether Jaroussky’s slender figure and his androgynous voice are evoking maternal feelings only. The combination of male attractiveness and a high-pitched voice, which effortlessly seems to master the most breathtaking passages, already caused a frenzy in Baroque audiences. Back then, it was the castrati who retained their boyish sopranos due to brutal mutilation. Moreover, the hormonal changes caused the singers often to be much taller than average, with huge chests that could contain air for minutes of coloraturas. Farinelli, Carestini, Caffarelli – they were the big stars of the opera world of the eighteenth century “They were tragic creatures, solely created for art,” Jaroussky explains; gods on stage, they were shunned in real life as freaks.

Their repertoire is sung again, for some years now, by countertenors. All of them completely intact males who sing with the so-called head voice. Every man who has ever tried to imitate the “Queen of the Night” for fun knows that men as well can flip their voices into high ranges. However, very few use it to pursue a musical career. Until a decade ago, countertenors were a rarity. “Nevertheless, in the meantime, every opera house also has a couple of Baroque works in their repertoire,” says Jaroussky. “And they cast them – as it originally was intended – with men.”

Perhaps it might still be strange to some when on an opera stage, the singer of Handel’s “Giulio Cesare” emits high coloraturas, but luckily, the time has come to say goodbye to our stereotypes of masculinity, says Jaroussky. “A few generations ago, men were supposed to be brave, not to cry, not to express their feelings. Now, we have strong women and sensitive men.” When Jaroussky speaks, his arms are often in a flowing motion, just in the same way as when he is singing on stage. It is not a pose. It rather seems like a constant struggle for truthfulness. The secret of his voice, Jaroussky explains as follows: “I don’t sing like a woman; I sing with my male sensibility.”

However, his “second voice,” as he calls his head voice, the Frenchman only discovered when he was 18. Until then, the son from a middle class family from the surroundings of Paris had learned to play the violin and the piano and was headed for the profession of a music teacher. When he heard a countertenor at a concert, the lanky boy immediately knew: “I can do that.”

Within a few years after finishing his vocal studies in Paris, Jaroussky ascended the throne of countertenors and continues to defend it up to this day, even if they are singers who are younger and perhaps technically superior to him. Yet no one combines emotional depth and youthful easiness as Jaroussky does, who admits that, generally speaking, there is something childlike to countertenors. “I’m probably not fully grown up.” As a kind of Peter Pan of Classical, he is jetting across the world for over ten years by now, recording one CD after another (around 30 by now), traveling to concerts on every continent.

However, he rarely sings operas: “On stage, you are wearing a costume, are an emperor, a God, an angel or a monster. For months, you only immerse yourself into this one production. It is very rewarding, but at the same time, very exhausting.” Jaroussky does not like to play roles; he prefers to face his audience without any makeup, rendering himself “defenselessly,” as he calls it,” to the music on the concert stage. Which is probably the reason why, after the first arias, the audience forgets to cough, and later, to breathe.

Now – he just turned 37 – a little bit of gray starts to mix into his dark temples. “I have about ten years left with this voice,” he says. “But the fascinating thing about singing is that you can only enjoy a voice now, at the very moment.” The times of extremely athletic, virtuosic castrato arias are reaching an end. He is planning to sing more Handel, Purcell, Bach, he says. “I used to be a little afraid of Bach. He is so perfect. At your own first note, you go to yourself like,‘Shit, I messed it up.’”

With his new CD and a tour with settings of poems by Paul Verlaine to music, Jaroussky has fulfilled a new project very close to his heart – Verlaine, enfant terrible of French literature of the 19th century, a genius driven by passions and addictions whose poetry inspired all of the renowned composers of France. Jaroussky’s voice fits perfectly into the unreal world of sound of Impressionism, even if none of the songs was written for the voice of a countertenor. “However, it has to be mentioned that most of what I sing was not written for my voice,” Jaroussky explains. A countertenor can be anything: soprano, mezzo or alto; the term actually only declares that a man is singing in his high head-voice.

Verlaine’s restless world, stirred by passions and drugs, however, is far away from the everyday reality of Philippe Jaroussky. “I’m not leading this kind of artist’s life that used to exist. When I’m traveling to my concerts, on the plane, I am sitting next to businessmen. I stay at the same hotels as them; at breakfast, I’m sitting there just as they are, with my iPhone on the table,” Jaroussky says, amused. “Maybe that’s why I am fascinated by Verlaine’s work.” The constant life on tour is not reality, he says. “Someone picks you up at the airport, someone hands you the keys to your hotel room, there is room service, everyone looks after you. And at some point, you realize that on long, lonely evenings spent in hotels, the internet has become your second partner.”

To get away from it all, the year before the last he took a sabbatical of eight months and traveled South America, Australia, Asia. Finally to have some time, for his boyfriend too. The other isn’t a musician, and therefore consistently has to step back behind the schedule of the singer who strictly keeps him out of the media hype. “What might sound strange: I didn’t sing during this time, for months. And I didn’t miss it,” Jaroussky says, laughing. It was comforting to know that for him, there could be an existence without his voice. From now on, he wants to take sabbaticals at regular intervals, he says. But first, he is picked up, the train to Berlin is leaving soon. Attentively, his agent leaves right behind him, carrying the cold remedy in a white plastic bag.

*Meike Schnitzler was glad to be able to listen to Philippe Jaroussky’s CDs for hours while she prepared the article. However, when she actually wrote it, she had to turn off the music – or otherwise she would never have finished.